Containment, Development, and the Fight for Freedom in Skid Row

This part is a deep dive into the history of containment, banishment, and neglect that have long characterized policing and governance of Skid Row. This is the violence that today’s data-driven policing programs help automate.

Skid Row is a vibrant community of poor and predominantly Black, migrant, Indigenous, and disabled people helping each other survive. It’s also where the city tests new forms of policing, surveillance, criminalization, neglect, and abandonment. This makes the empowerment and liberation of Skid Row residents crucial in the broader fight to abolish these systems everywhere.

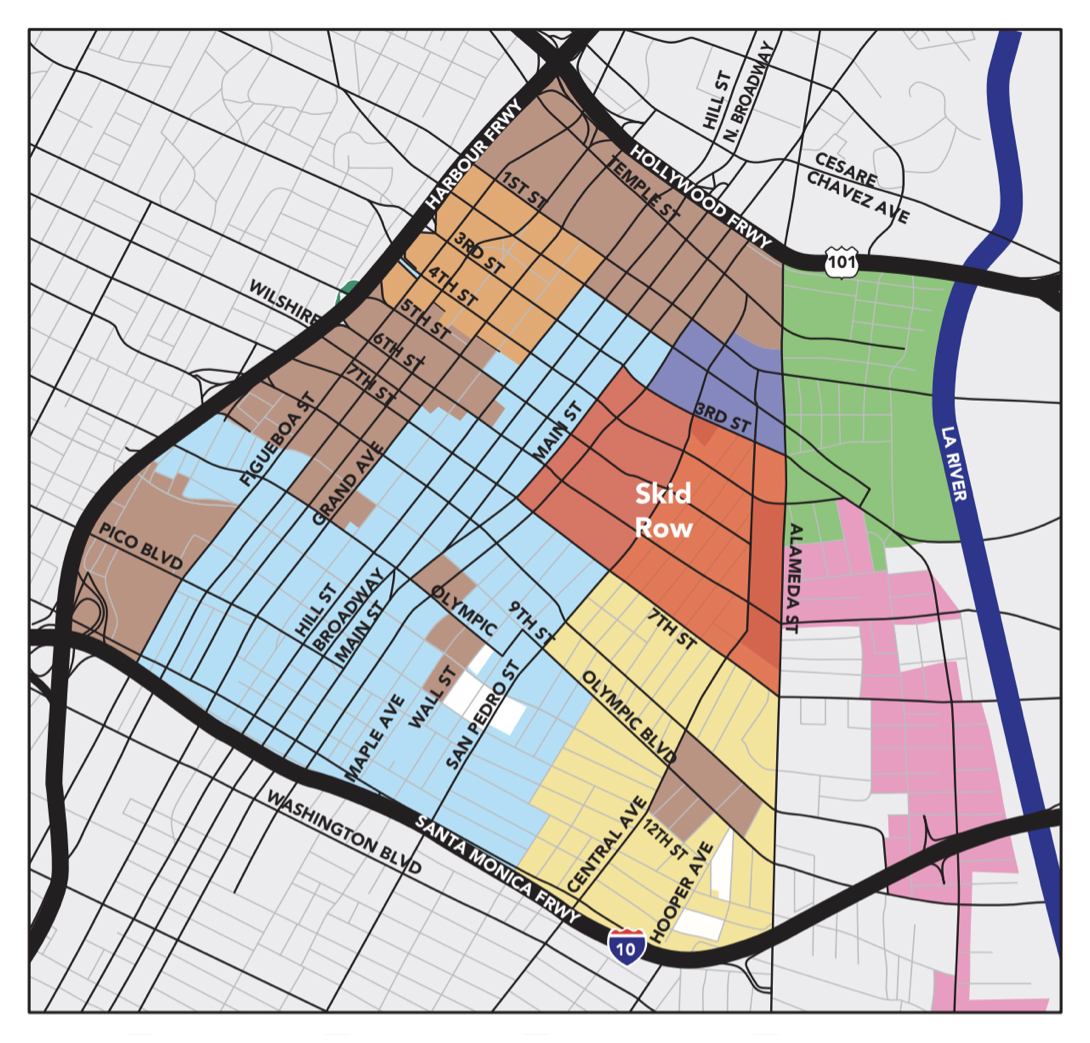

This part proceeds by examining the role of surveillance and criminalization in different efforts to contain as well as transform downtown L.A. over the years, with a focus on policing’s relationship to three efforts to transform Skid Row through land use and “redevelopment” plans: the Bunker Hill Redevelopment Plan of 1956; the Central Business Redevelopment District Project of 1970; and the New Downtown 2040 rezoning plan. When viewed alongside prior plans, the currently unfolding 2040 plan looks like yet another run at the same strategy of rezoning downtown to make space for market-rate housing instead of creating housing for the thousands of people living in self-made homes. But this time around, police, city officials, and real estate developers have new tools for coordinating this conquest: these entities are now highly organized through data-driven policing tactics honed over the years, including “broken windows” policing, “community” policing, the Citywide Nuisance Abatement Program, Compstat, and “predictive” policing. All these tactics are woven together in LAPD’s new Data-Informed Community-Focused Policing framework.

This part’s first half, titled The Skid Row Compromise: “Preservation” and Blight, looks at how city officials through the years leading to the late 1990s accepted arrangements to allow a population of poor people to remain in the city center while also working to contain and criminalize this community. Although some of downtown’s residential hotel buildings were nominally “preserved” in this period, the city also spent the same time refining both the operation and inputs of a nuisance abatement program that, when officially launched in 1997, targeted 11 central city residential hotels in the name of community policing. As Bill Bratton took over LAPD in 2002, policing of Skid Row expanded from violent sweeps backed by brute force to similar brutality submerged in multi-agency coordinated attacks to criminalize residents through “broken windows” policing and to dismantle the city’s last vestige of affordable housing. The second half of this part, titled Automation of Banishment: New Technologies, Old Patterns, looks at how data systems and notions of “community policing” expanded coordination between police, city agencies, developers, and businesses invested in displacement and banishment of Skid Row residents. A close look at these tactics and technologies of data-driven policing reveals a system of enhanced coordination to share information about the community in order to map and enact banishment block by block.

Together, these two periods are linked by the logics of extraction that have always guided conquest, colonization, and racial capitalism. It might be difficult at first to see how “extraction” operates for a community as materially deprived as Skid Row: what can you extract from people who appear to possess so little? The answer is land. And in order for that extraction to be profitable, the people present on that land first needed to be intentionally harmed and neglected by the state, via what we can call “organized abandonment” from analysis of urbanization as well as today’s prison-industrial complex [120] and “dependent underdevelopment” from analysis of European colonization. [121]

Through neglect and criminalization of Skid Row’s residents, the city created conditions where real estate investors and speculators now stand to extract massive profits from “redeveloping” Skid Row, an area that investors have long eyed as an extremely valuable as well as an “undervalued” frontier for gentrification. This “undervaluing” required decades of containing, criminalizing, and neglecting Skid Row’s residents. And the area could not be targeted for the kind of coordinated, data-driven state violence it now faces without years of surveillance and policing. Throughout all this history is a continuous effort by the city to secure conditions of chaos and instability for residents of Skid Row in order to banish and displace them.

This is a story seen throughout the history of colonization and conquest. As always, white wealth and power grows via extraction from the communities that have always received the least from the white supremacist state while also suffering its worst violence, policing, and surveillance.

The Skid Row Compromise: “Preservation” and Blight

Skid Row sits in the middle of downtown Los Angeles, a vibrant community that has long been a refuge for people deemed disposable by the city, particularly poor Black people and other people of color. The community grew over the years due to various economic booms and busts within the agriculture, petroleum, and automobile industries, and through the decades the area was deliberately configured to contain and restrict the city’s most banished people.

At the same time that Skid Row served as a refuge for the city’s poorest residents, it has been a target of developers who have continually coordinated with city officials and police to remove this community from the profitable city center. “Blight” has been a key concept in this approach, used by the city and developers to condemn areas where poor people lived in order to redevelop them for profitable commercial and housing markets. The term “blight” is rarely defined with any precision, and courts have granted municipal officials wide latitude to come up with definitions, including to qualify for federal funds or local tax breaks for redevelopment projects. For example, as a Philadelphia planner proposed in 1918, a blighted area "is a district which is not what it should be.” [122]

“Redevelopment” and Containment

By the 1940s, the Bunker Hill area of downtown had the highest population density of anywhere in Los Angeles, and the majority of dwelling units were tenant-occupied single rooms with no utilities, facilities, or running water. Police, health department, and fire department statistics classified the area as criminal, disease-ridden, and a fire hazard. [123] To address areas like this, in 1945 the California Legislature enacted the Community Redevelopment Act, which empowered local governments to target “blight'' through development, reconstruction, and rehabilitation of residential, commercial, industrial, and retail districts. [124] The Bunker Hill Redevelopment Plan (BHRP) of 1956 was the first intensive urban renewal project pursued by the city’s new Community Redevelopment Agency (CRA). [125] The effort was initially shaped and influenced by business leaders who hoped it would expand commerce and industry. But these supporters balked when the projects looked to redevelop blighted locations into improved housing for the inhabitants, replacing informal and dangerous living conditions with new public infrastructure. [126]

Through the years CRA would evolve to preserve the supply of housing for very low, low, and moderate income households. Throughout the 1960s, however, many of the contested single room occupancies (SRO) fell into disrepair. The city continued to increase enforcement of building and safety codes for the remaining SROs, and many owners found it cheaper to demolish the buildings rather than comply with work orders to improve conditions. [127] As a result, the affordable housing provided through SRO buildings were reduced by half during this period. [128] In 1965, the BHRP had about 6,000 people who needed to be relocated, and a total of 2,424 relocation payments were made in the amount of $24 each. The adjacent communities of Skid Row and Westlake subsequently saw an influx of impoverished elderly individuals, while many of those “relocated” ended up homeless. [129]

In the late 1960s, City Council moved to “clean up” Skid Row with new laws that made it impossible to be poor and unhoused in the city. In 1967 the city enacted what remains its most vicious ordinance criminalizing homelessness, Municipal Code 41.18. This law states that “no person shall sit, lie or sleep in or upon any street, sidewalk or other public way.” On top of that, police also increased arrests for petty crimes like public inebriation—which, in 1975, became the single most common “crime” for arrest in Los Angeles. [130]

Decades later, draconian enforcement of crimes of poverty would be theorized as “Broken Windows policing,” introduced in part 2 of this report as a component of data-driven policing. But the practice went as far back as the 1900s, for example, when the city’s jail population rose sharply due to mostly white males being jailed for public order offenses like “vagrancy.” Concentrated in the downtown area that later became known as Skid Row, “Los Angeles’s systematic jailing of transient laborers incited the first significant expansion of the city’s carceral infrastructure, with overcrowding leading to two new city jails, a new county jail, and a stockade at Lincoln Heights.” [131]

The assault on Skid Row expanded with the Central Business Redevelopment District Project, which was based on a report released by the Community Redevelopment Agency in 1972 that had become known as the “Silver Book.” Produced as a glossy coffee-table book by a team of urban planners and architects, the “Silver Book” plan proposed a complete restructuring of the district by 1990, [132] with Skid Row to be eliminated and replaced with a one-block area providing information regarding social services. [133] After that plan met opposition, in 1976 the newly elected mayor Tom Bradley, together with a “large tent” coalition including the Los Angeles Catholic Worker and Legal Aid Foundation [134] as well as residents of other neighborhoods who didn’t want Skid Row expanding into their areas, offered what they called the “Blue Book” plan as an alternative. [135] This plan’s formalization of Skid Row as the home of the poor and unhoused community became a part of the city layout. [136] The CRA also worked to rehabilitate buildings and secure affordable housing through the establishment of the SRO Housing Corporation in the 1980s. [137]

Baked into the Blue Book plan to “save” Skid Row was also targeted criminalization in what would become known as the neighborhood’s “buffer” zones. The Blue Book plan expressly outlined this goal of containment:

“With public restrooms, benches, and pleasant open spaces within the contained area of Skid Row, the residents might be inclined to confine their activities to the immediate area. That section would serve as a magnet to hold undesirable population elements in Skid Row, not against their will but of their own accord. Strong edges will act as buffers between Skid Row and the rest of the central city. When the Skid Row resident enters the buffer, the psychological comfort of the familiar Skid Row environment will be lost; he will feel foreign and will not be inclined to travel far from the area of containment.” [138]

The Blue Book plan also aimed to stabilize the provision of low-income housing, particularly SRO hotels and social services in Skid Row. This was a compromise between, on the one hand, downtown investors and public officials seeking to displace impoverished people away from profitable downtown redevelopment projects and, on the other hand, advocates who sought to protect the unhoused community and increase access to shelter space and services. [139] This plan would allow unhoused people to “live freely as they choose'' within boundaries also serving to “contain” disruption outside the developing and gentrifying areas of downtown.

Sweeps and Criminalization to “Sanitize the Area”

The Blue Book containment plan never fooled Skid Row residents into believing that city officials, developers, and police would end the assault on their community. Under the containment strategy, Skid Row became a zone for targeted policing as well as neglect and exploitation. In the compromise brokered to “preserve” Skid Row, p olicing and social services served as tools of deliberate underdevelopment and dependency to strip people of autonomy and community control over land.

While containment helped to shore up resources for unhoused and poor residents, it also facilitated carceral policies and demonization of the community, along with millions of dollars in public investment to construct mega-shelters. Not only did these shelters proliferate and entrench themselves in lieu of policies that secured real housing, wealth, or land ownership, they now “contribute to carceral strategies that widen the revolving door of poverty from the shelter bed to the jail cell.” [140]

The coming of the 1984 Olympics accelerated these harms. By this time L.A. was already dubbed ”the homeless capital of the United States” and rents were skyrocketing. “We’re trying to sanitize the area,” an LAPD captain announced a week before the Olympics began. [141] Unhoused residents of neighborhoods where tourists were expected were arrested, expelled to faraway detox centers, or forced to move while their belongings were destroyed. And just as draconian arrests of unhoused people had required the construction of new jails in the early 1900s, the county also built an “overflow” jail with a special computer system to automate processing and prosecution of mass arrests.

In May 1987, LAPD chief Daryl Gates declared Skid Row’s sidewalk encampments “intolerable” and announced that hundreds of unhoused residents had a week to get off the streets or face arrest. Gates had been police chief since 1978 and would remain in power until 1992. A notoriously racist police official, he had once claimed that Black people died more frequently from police chokeholds because they were physiologically different from “normal people.” [142] Under his tenure LAPD also spied on community groups, activists, and public officials through the Public Disorder Intelligence Division (PDID) and created the Special Weapons and Tactics (SWAT) unit, which used battering rams on residential neighborhoods. [143]

Like LAPD chiefs before and after him, Gates was keen to use demonization of unhoused people to expand his powers. Gates made it clear that the city's objective was to eradicate poor people rather than address their poverty. Though civil rights attorneys attempted to address the human rights violations Gates was carrying out, a state Superior Court judge ordered that the city only needed to give a 12-hour notice before conducting sweeps. The sweeps commenced in June 1987. [144] While very few people were arrested, many people left Skid Row due to the threat of police violence and arrest. [145] These attacks only intensified over the years.

Blight and Targeting of Skid Row’s SRO Hotels

Along with unhoused residents, Skid Row is also home to several single-room occupancy (SRO) hotels that offer some of downtown’s most enduring housing options for extremely poor tenants. These residential hotels typically feature small rooms with minimal furniture and often a shared bathroom. Historically SROs were built to shelter people who moved to the inner cities from rural areas in search of work. Because SROs continue to house the very poor, they are often demonized by developers and investors who characterize residents as a public nuisance. Over the years, these buildings were deliberately neglected and blighted, empowering the city to target them as nuisances using criminal and property law.

Over the years the reduction of SROs has fueled homelessness in the city. According to a former high-ranking HUD official who was made administrator for the city CRA in 1986, the reduction of federal funding support for SROs during the 1980s is what drove many people to the streets. [146] Meanwhile, repeated attempts by the City Council to preserve SROs had been ineffective and even incentivized property owners to let the buildings deteriorate or fall victim to fires. [147] By July 1987, a month after the Daryl Gates assault on Skid Row, Mayor Bradley proposed a moratorium on demolition of SROs and created a special committee to formulate a lasting shelter policy for unhoused people. [148] Othering of unhoused residents continued within the committee, with the group’s chairman Harold S. Jensen asserting that there was “a distinct difference between the SRO community and the homeless community” in that “the SRO community that has existed there historically is relatively stable, very poor and with very limited resources, but it is not a threat to neighboring uses.” Jensens’ distinction was that “the invasion of the homeless threatens both the stable SRO population and the businesses in the immediate area.” In turn, the committee recommended tighter police security on Skid Row.

In late 1989, City Council voted to extend a moratorium against the demolition of the hotels for five years on Skid Row and three years citywide. The attack on SROs was far from over though, and the city soon turned to another approach for targeting these homes rather than demolishing them outright: CNAP, introduced above in part 2. As CNAP launched in 1997, the forces transforming downtown ramped up again with the 1999 passage of the Adaptive Reuse law, which permitted the conversion of vacant commercial structures into new residential buildings. In turn, investors – including the county’s Economic Development Corporation, a nonprofit public-private partnership – funded the creation of thousands of units of high-income housing, predominantly lofts, condominiums, and luxury apartments in areas that were previously a refuge for poorer communities.

Around the same time, city zoning officials identified 11 downtown residential hotels in Skid Row as public nuisances. The hotel owners were ordered to renovate the buildings and to install security cameras. [149] While some of the complaints leveled against residential hotel buildings reflected efforts by tenants to improve their living conditions, the pressures on hotels to undergo costly renovations also served the interests of businesses and city officials who wanted these hotels closed altogether. The Los Angeles Community Action Network and others successfully lobbied city officials to institute a moratorium on the conversion of SRO housing units into condominiums or luxury apartments. In 2008, this moratorium expanded and became permanent, protecting close to 19,000 units across the city, an important victory for low-income residents. [150]

More recently CNAP has become part of data-driven policing programs like Operation LASER, as we introduced in part 2 above. LAPD also targeted some of Skid Row’smost vulnerable SROs as Anchor Points under LASER, subjecting these locations toextreme policing and other displacement strategies.

Automation of Banishment: New Technologies, Old Patterns

Starting in the mid 2000s, LAPD launched a series of data-driven policing programs that over time integrated “broken windows” policing, community policing, and predictive policing programs. These programs built on the city’s past practices of containing Skid Row and enabled enhanced coordination of community partnerships by city officials, police, public sector agencies, and wealthy stakeholders while using military-grade surveillance technologies and counterinsurgency tactics to map banishment block by block. These policing tactics are serving to transform Skid Row as part of the buildup to the city’s latest downtown “redevelopment” scheme, the Downtown 2040 Plan.

In 2006, “broken windows” policing – introduced in part 2 above – ramped up in Skid Row as the Safer Cities Initiative (SCI) launched under Bill Bratton’s leadership. At an annual price tag of $6 million, LAPD deployed an expansion of fifty patrol officers as well as thirty narcotics, mounted, and bicycle officers into the .85 square mile area of Skid Row. During the first two years of SCI, “LAPD conducted 19,000 arrests, issued 24,000 citations as well as incarcerated 2,000 residents, and dismantled 2,800 self-made housing units” in Skid Row, a community of around 12,000 to 15,000 residents at the time. [151] A 2008 study by law professor Gary Blasi and sociologist Forrest Stuart compared the frequency of certain offenses occurring where SCI was deployed to other parts of Central Division that were not targeted in the same way. [152] Their study concluded that there is no statistically significant relationship between SCI and reductions in overall rates of serious crime. [153]

At the same time that SCI served little purpose besides oppression of Skid Row residents, LAPD Chief Bill Bratton realized the importance of organizing and strengthening the business communities to garner support for the program. Bratton lobbied city leaders to hire one of the main theorists of “broken windows” policing, George Kelling, who organized monthly meetings throughout 2002 and 2003. These meetings brought together city officials, downtown developers, and representatives from the mega-shelters of Skid Row to collaborate on policing of Skid Row. [154] Those meetings later evolved into “Skid Row Safety Walks” organized by local BIDs. As part of these walks, public officials, law enforcement (including sometimes Bratton himself), judges, students, academics, local business owners, social service providers, and the media walked through the streets of Skid Row to gaze at the community and discuss the problems they perceived. [155]

This same period also saw an expansion of street policing by BIDs. As discussed in part 3 above, BIDs raise money from local businesses and developers to hire private security guards who can enforce municipal ordinances. In Skid Row, BID patrols funded by the Central City East Association (CCEA), used their “mostly white guards” to criminalize “homeless behavior in Skid Row through citizen arrests, detainment, assault and battery, destruction and confiscation of homeless property, harassment, and false grounds for imprisonment.” [156] In a lawsuit filed by Skid Row residents against CCEA along with the BID’s private security company, the BID hired George Kelling as an expert witness. Kelling’s testimony articulated the logic of broken windows policing and the prioritization of “real property” to defend the BID’s practices of confiscating the property of unhoused people in Skid Row:

“Disorder as a result of leaving personal property on public sidewalks in an area interferes with the uses of real property in the area, produces a hiding place for illegal behavior to be conducted, threatens the viability of the neighborhood, increases citizens’ fears and lowers the social norms in the area thereby reducing the quality of life.” [157]

BID patrols stored the property they confiscated on behalf of their real estate developer and business funders in a 20,000 square foot facility donated by a CCEA board member and downtown developer. LAPD used this same private facility to store property they confiscated as well. [158]

As noted in part 1 above, CCEA also paid for and built some of the Skid Row surveillance architecture that feeds data-driven policing, including a 2005 donation of $200,000 worth of CCTV surveillance cameras that would be controlled by LAPD. In 2011, CCEA’s executive director described this system as “a network of cameras gifted to the LAPD.” [159] LAPD Commander Andrew Smith, who oversaw the Central Division for several years, once used the language of community policing to explain how BID patrols and surveillance-sharing act as a “force multiplier for our officers.” He added: “Those folks are terrific to work with.” [160]

The Downtown 2040 Plan

In May 2017, journalist Adrian Riskin published records of communications between downtown BIDs and city officials. The records show Blair Besten, Executive Director of the Historic Core BID, emailing Bryan Eck, a policy planner at the city planning department in November 2016 with policy and rezoning suggestions that incentivize mixed income and mixed project development throughout the downtown area, including Skid Row. [161] Though it is not clearly articulated within this email, it seems very likely that this is all in relation to the Downtown Los Angeles Community Plan, also described by the city as DTLA 2040. [162]

DTLA 2040 is a proposal to update the zoning plans for Central City and Central City North, with drastic changes to Skid Row. The plan endeavors to add 70,000 housing units to make room for a projected 125,000 new residents downtown. This rezoning will enrich developers who have spent years plotting and closing in on Skid Row, empowering them to extract wealth generated based on decades of blight that kept Skid Row property values low. In other words, this is a windfall once again allowing wealthy capitalists to enrich themselves off the historical neglect of Black and brown communities.

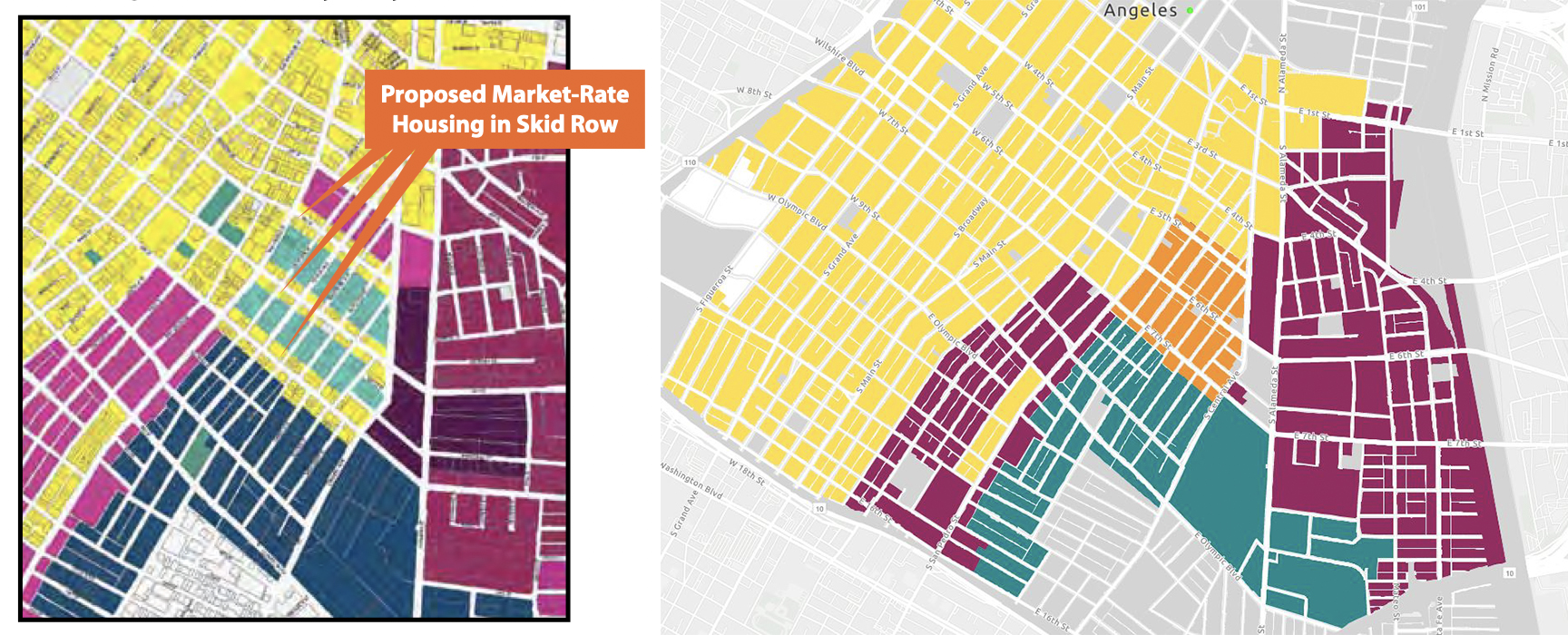

The plan formalizes and expands the displacement that has been encroaching on Skid Row. At present, the eastern half of Skid Row is zoned for light manufacturing, with non-residential structures used as warehouses, seafood wholesalers, storage facilities, and other industrial and logistical purposes. But gentrification has been pushing into that eastern edge, with old factories and structures becoming refurbished lofts and artist-in-residence studios because the area contains large parcels controlled by single owners who can “swiftly decide to change use of the land.” [163] Meanwhile, Skid Row’s western half is zoned as community commercial and a “medium to high” residential zone, which would allow a density of 56 to 109 family dwelling units per acre. [164]

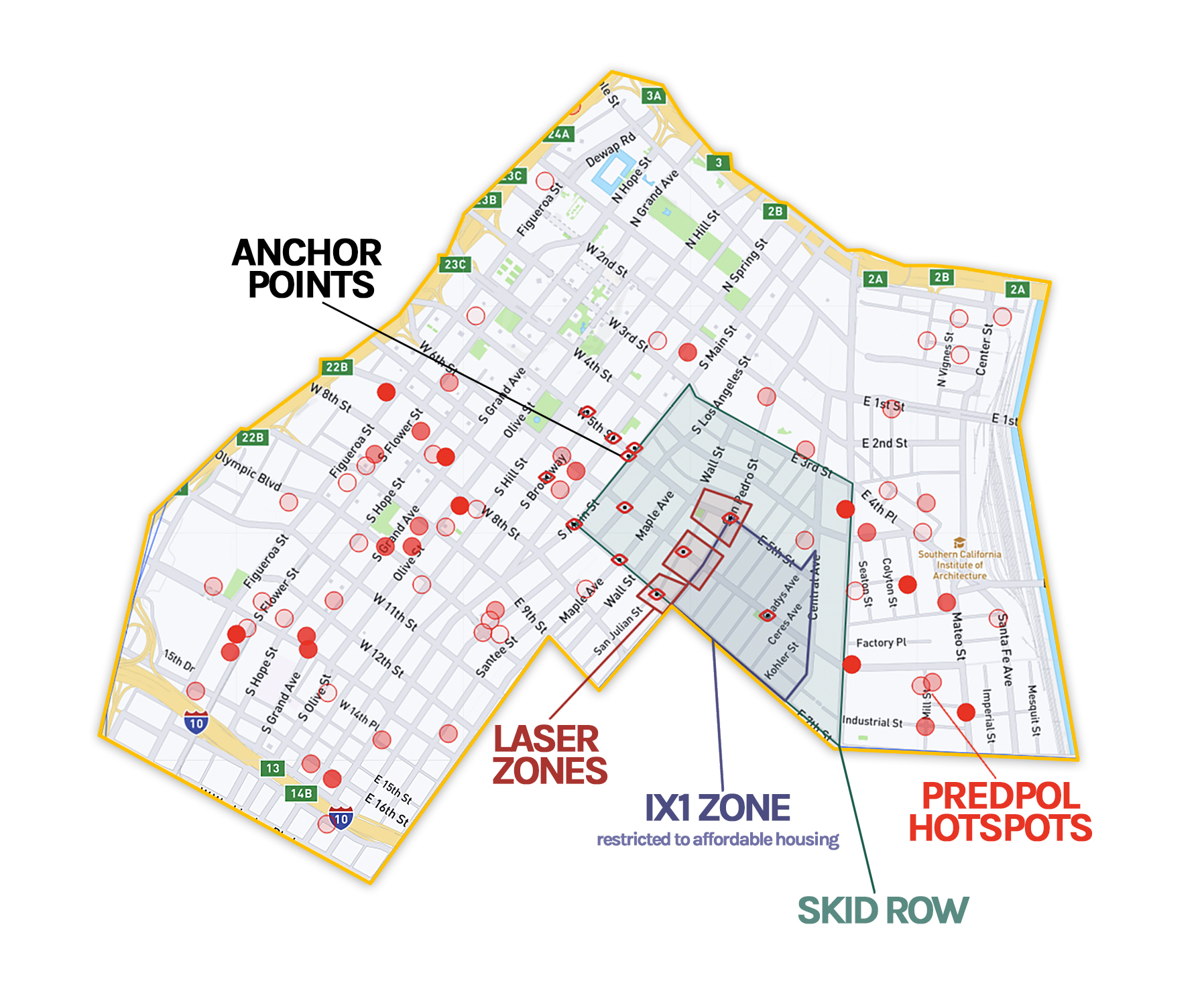

The initial version of the 2040 Plan proposed in 2018 would have rezoned all of Skid Row to allow market-rate housing, including along Skid Row’s primary corridors of 5th, 6th, 7th streets, with the goal of “creating corridors that link the downtown skyline with a new fashion and arts district.” [165] After housing advocates protested this assault on Skid Row’s low-income housing stock, a new zone was carved out solely for affordable housing, labelled the iX1 section and bounded by 5th Street to the north, 7th Street to the south, Central Avenue to the east, and San Pedro Street to the west. [166] While this new zone preserves some affordable housing compared to the initial proposal, the protected area is less than half the size of Skid Row today. [167]

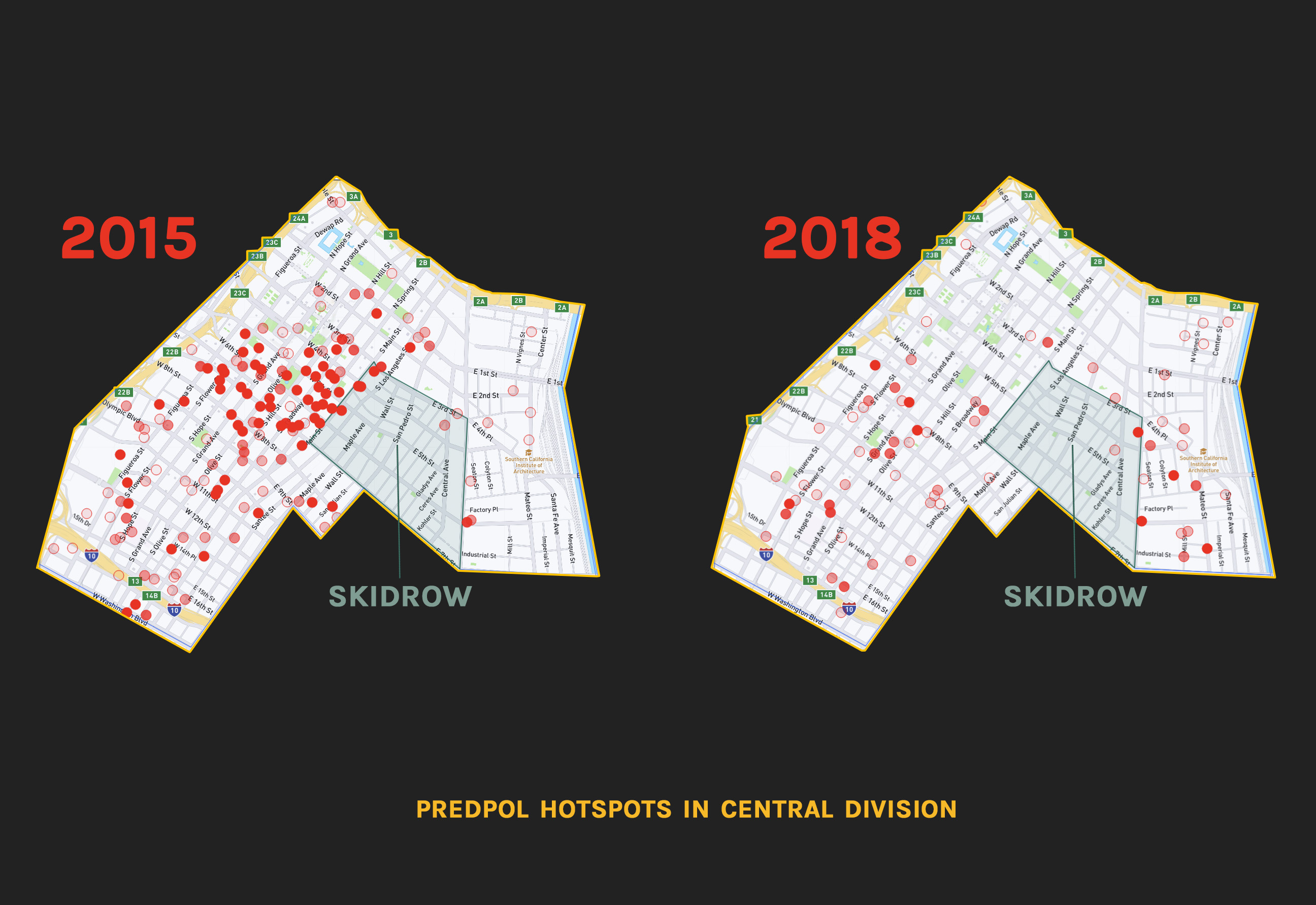

When considered in the history of past redevelopment plans, the 2040 plan appears to be another attempt at the same strategy of rezoning and redevelopment to make space for market-rate housing instead of prioritizing the creation of housing for the thousands of people who already live in self-made homes. But this time around, the state and its collaborators have new tools for coordinating their conquest: city officials, developers, and police are highly organized through data-driven policing tactics honed over the years, starting with the PredPol and LASER predictive policing programs. When we studied the locations these programs targeted, we found that the data-driven policing patterns closely matched the city’s goals for transforming Skid Row, right down to the block level.

PredPol: Quarantine and Buffer

Examining the details of predictive policing’s operation shows how these programs helped lay the groundwork for the city’s latest assault on Skid Row community. PredPol was implemented downtown in summer 2015. [168] We created the maps of PredPol hotspots below based on records we obtained via the PRA. [169] The dominant argument against PredPol often centers the algorithms, citing bias in the algorithms as well as a feedback loop from recycling police data. [170] The assumption would be that more reports of crime would mean more hotspots in Skid Row, which has long been the target of the city’s most aggressive policing as well as the area that mainstream media, LAPD, and city officials continually categorize as crime-infested.

Operation LASER: Policing a “Bastion of Difference”

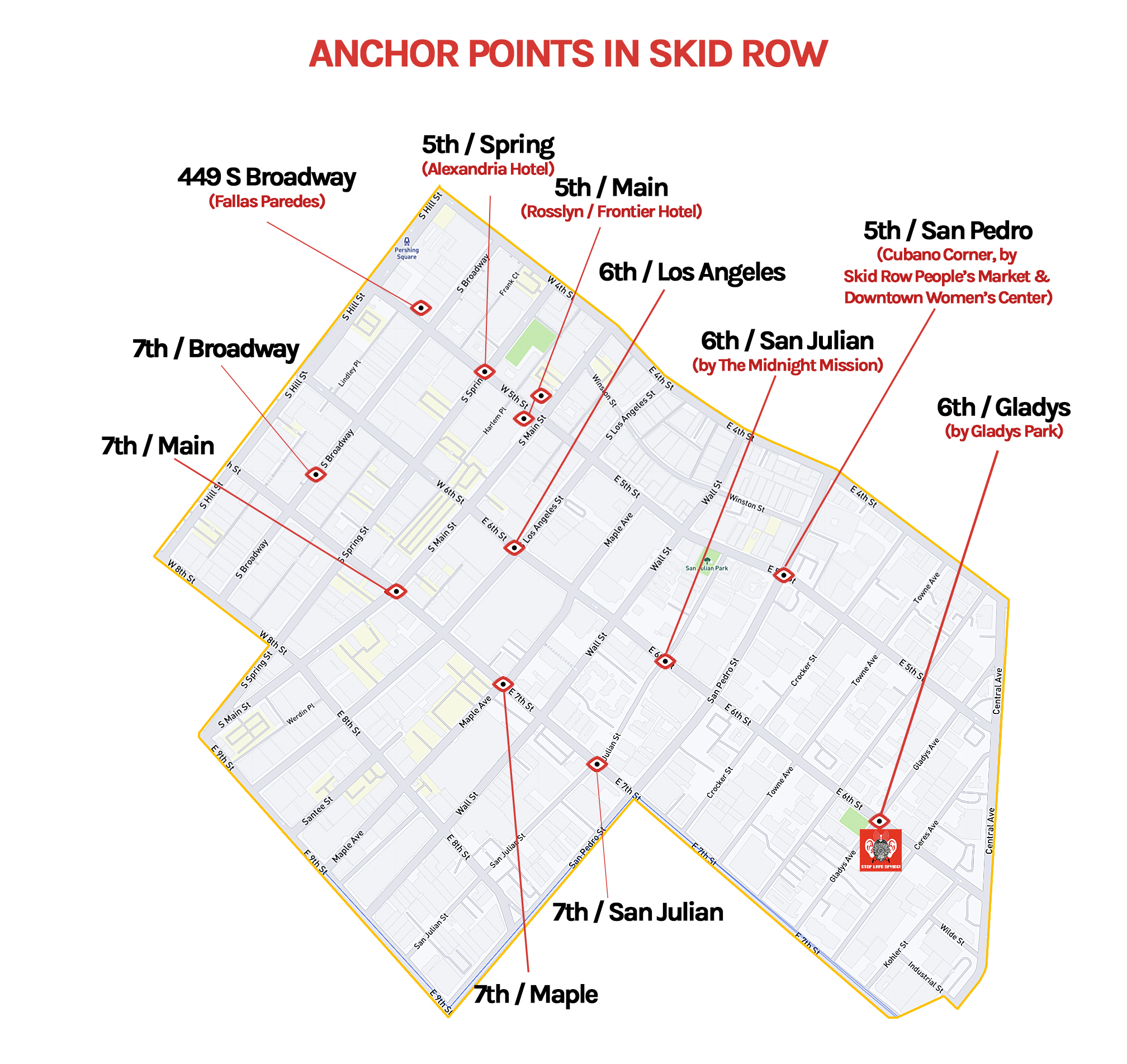

Records obtained through a PRA request we filed in November 2018 revealed that some of the locations designated as Anchor Points in Operation LASER included churches, hospitals, high schools, universities, housing shelters, metro stations, entire 500 feet by 500 feet areas, as well as shopping centers, malls, and apartment complexes. The records included an LAPD document of Anchor Points from the Central Division labeled “BID anchor points.” While the precise role of BIDs in LAPD’s targeting of these locations is unknown, this appears to be yet another way BIDs were integrated into policing.

The targeting of these locations cannot be divorced from the long history of dismantling residential hotels and other architecture that Skid Row residents depended on. As explained earlier, LAPD intervention at Anchor Points include abatements and evictions, changes to licensing and conditional use permits, and changes in environmental design. Many of the locations marked “BID anchor points” by LAPD are where residential hotels either exist or existed and where new luxury development is now occurring. They are also all in areas where market-rate housing will be allowed under the 2040 Plan. These Anchor Points are shown on the map below.

All these locations have been sites of extreme contestation over the years. For example, the Anchor Point at Spring and 5th Street is the site of the Alexandria Hotel. Built in 1906, the Alexandria was regarded as the city’s “most elegant hotel before the construction of the Biltmore in 1923.” [172] In 2006, the hotel was purchased by developer Robert Islas, who created uninhabitable conditions in order to evict low-income and disabled residents, including no hot water for weeks at a time, and and facilitate renovations funded in part by the Community Redevelopment Agency, which we introduced earlier in this section. Around 100 residents of the Alexandria were evicted without relocation assistance before tenant organizing efforts led by the Los Angeles Community Action Network (LA CAN) helped hold the CRA and other city agencies responsible for enabling Islas’s abuse. [173] A lawsuit filed by LA CAN settled with city officials and the developers agreeing to pay almost $1 million to house and compensate residents who had been evicted, as well as putting in place new tenant protections for all CRA-renovated buildings. [174]

Another Anchor Point that has been a significant site of contestation and struggle is 112 West 5th Street, which is the Rosslyn Hotel. This mixed-use hotel continues to supply affordable housing and takes section 8 vouchers. The Rosslyn Hotel stands across the street from 451 South Main Street, another Anchor Point and the site of an older hotel built in 1914 that originally had the same name. Together these two buildings, connected by an underground tunnel, were at one time the largest hotel in the entire Pacific Coast, with 1,100 rooms and 800 baths. [175] In the 1970s, the Frontiera family purchased the buildings and renamed 451 South Main Street as the Frontier Hotel. At the time, both hotels served low-income residents as SROs. In 2009, the Frontier was renamed the Rosslyn Lofts and the units are “split between low-income "micro loft" apartments and market rate luxury lofts.” [176]

According to our conversations with LA CAN organizer General Dogon, who was born in Skid Row and has lived here all his life, the streets around these hotels began to transform starting around 2002. Dogon told us that nearby street lighting suddenly changed, now artfully done unlike the lamps in front of the SROs, which resembled the prison floodlights of San Quentin. Next came street signs marking the area as “Gallery Row,” a name that arrived as news to longtime residents. Then, in a show of just how stark the gentrification and discrimination was, an “Art Walk” began to take place at the same time the city also created a Drinking in Public (DIP) task force that would cite Black and brown residents in the afternoons, especially on Art Walk days, then almost always disappeared in the evening when gentrifiers at the Art Walk were drinking and walking around.

The Frontiera family that owned the Frontier and Rosslyn has been described as “instrumental in fostering the art gallery scene that is now a staple of the area.” [177] Today the owner of the hotels Rob Frontiera also has a reputation for racist and predatory landlord practices, in particular harassing, intimidating, and exploiting low-income residents in order to extract wealth through market-rate tenancy. General Dogon along with another LA CAN organizer Steve Diaz, who for years lived in the Frontier Hotel, told us that residents often referred to it as the Jim Crow Building. Now called the Rosslyn Lofts, the building had two entrances, one on the side of the building for low-income tenants that resembled the lobby of a jail and featured large notices about what tenants could and couldn't do, and another far more luxurious one at the front of the building for new market-rate tenants. Market rate units were located on the top floors, with everything below the ninth floor used for affordable housing. Hot water was often reserved solely for wealthy tenants.

Another predatory and illegal practice that Frontiera used was the “28-day shuffle.” This refers to SRO landlords moving residents in order to prevent them from establishing tenant rights (including rent stabilization), which generally set in after 28 days of residency. Residents would have to pick up all their belongings and check out and then check back in, usually without explanation of what was going on or why. In response, LA CAN and other groups “waged a campaign to educate hotel residents about the practice and to force officials to take action against it,” helping residents send about 300 complaints to the city housing department. [178] When confronted about the practice, Frontiera stated in 2006: “We ran it all past the Housing Department and the city attorney’s office.” [179] But the tenant organizing succeeded in forcing the city to sue Frontiera, who settled the case for a $1 million fine. The bulk of that money was used to pay for “relocation restitution to more than 200 former occupants of the Frontier Hotel who were moved out to make room for the conversion of the building to upscale lofts.” [180]

Policing and CNAP played a crucial role in this assault on low-income housing at the Rosslyn and Frontier. According to former residents we spoke to, the fact of people “hanging out” near the hotels was used to trigger CNAP enforcement or at least referenced as the basis for it. The Frontier’s CNAP-related restrictions included strict rules on entry, and CNAP conditions apparently featured a mysterious list never disclosed to tenants but constantly referenced by the landlord to convince tenants to move down from the top three floors in order to vacate in exchange for market rate rooms. Businesses including a diner on the ground floor left the building, and in the block surrounding the hotel many essential and affordable shops and restaurants never came back, replaced with more expensive retail for new residents.

While tenant organizing has helped secure some measure of protection for longtime residents, criminalization has continued through data-driven policing. When asked about “crime” in the area during the time when these locations were marked Anchor Points, both General Dogon and Steve Diaz explained how these were not places where crime was happening. Instead, as Dogon put it, “Poverty was happening. Survival was happening here.” And as Steve explained, “This was not the bastion of crime. This was a bastion of differences – a bastion of lack of resources.” Data-driven policing automates enforcement of these differences, applying the longtime Skid Row policing strategies of containment and banishment at the corner-by-corner and person-by-person level.

Steve also characterized the Anchor Points as “terror” zones, and Dogon narrated the displacing effect of this violence, including how brutal “broken windows” policing around these locations forced people to "scatter" from Skid Row. Other Anchor Points in Skid Row are also significant locations for the neighborhood’s containment, displacement, and criminalization. For example, the Anchor Points at South Main and 7th and at 6th and Los Angeles are two of the main corridors leading into Skid Row, both situated in the historic buffer zones. Another Anchor Point at 6th and San Julian is where the Midnight Mission – one of the area’s oldest shelters, founded in 1914 – is located, and the Anchor Point at San Pedro and East 5th Street is surrounded by the Brownstone Apartments SRO, the Downtown Women's Center, the Gateway Apartments SRO, and the Skid Row’s People Market.

Our PRA requests also asked for LAPD procedures for designating Anchor Points. The documents we received revealed extreme inconsistencies. Only some points were even recorded in LAPD’s database, leaving out points that show up in other police documents. [181] As for selection criteria, while some divisions defined Anchor Points as places that generate or attract violent crime, others looked only at thefts, and while some divisions relied solely on calls for service, others solely used crime data. [182] The application of criteria also varied wildly. One location was deemed an Anchor Point based on having four calls for service and no crime reports or arrests over an entire year. [183] Meanwhile other divisions simply listed notes like “transient encampments, narco” as the basis for marking an Anchor Point. [184] Some divisions even modified the data to make selections, [185] and some used conflicting criteria within the same divisions. [186] Additionally, some locations were marked an Anchor Point for as little as two months while others were marked for over two years. [187]

Overall, while the selection of these “data-driven” policing locations was by no means impartial, they also were not random. Rather, they help automate the city’s longstanding approaches to policing. Skid Row is the clearest example of that, with Anchor Points clustered around residential hotels and social service agencies. Our PRA requests also revealed a manual of proposed LASER zones for 2018, showing LASER zones running along the 5th, 6th, and 7th Street corridors, stretching from just west of San Julian Street to just east of San Pedro Street. This area is the heart of Skid Row, where social services are dispensed, where many SRO hotels still stand, and where shelters are located, as well as large areas where people have made their homes on the street.

Automated Banishment and Skid Row’s Fight for Freedom

The map below shows Skid Row’s “predictive policing” locations combined with the IX1 zone in the current 2040 rezoning plan. When the PredPol hotspots, Anchor Points, and LASER zones are all combined, what emerges is a coordinated assault on Skid Row. Together the Skid Row containment strategy and PredPol operated to quarantine residents in heavily policed borders as luxury development pushed in. Inside that containment zone, Anchor Points and LASER zones were how police worked to brutalize and banish people at locations targeted for gentrification. At the same time period when these “predictive policing” strategies were deployed in Skid Row, city planners began meeting to rezone the area in summer 2018. [188] This rezoning plan, which in its current form drastically shrinks Skid Row, proposes market-rate housing in the exact stretches of 5th, 6th, and 7th streets that LAPD earlier in 2018 had marked LASER zones and Anchor Points.

Even as the 2040 plan’s rezoning details remain subject to contestation and negotiation, the data-driven policing apparatus has already been in motion to extract and eradicate the community. But as this latest displacement plan unfolds, Skid Row residents are organized to fight back, long familiar with moves like this from the city, developers, and police. The Skid Row Neighborhood Council Formation Committee (an entity continuing the fight to form local democratic representation in Skid Row despite the oppositional efforts from developers and local BIDs) sent over 600 pages of public comment to the planning department condemning the rezoning plan, [189] and the Skid Row Now and 2040 Coalition (comprised of the Los Angeles community Action Network, Los Angeles Poverty Action Department, and the Inner City Law Center) announced the following policy demands: [190]

● No Net Loss – All existing units must be protected with a No Net Loss policy to ensure baselines of affordable housing units remain downtown.

● Inclusionary Zoning – While the No Net Loss would preserve the current baseline of housing, more investment is needed to build housing for residents who currently lack homes, through an inclusionary zone requirement of 25% set aside to generate 7,000 new units of Affordable (Low Income) Housing.

● New funding sources for affordable housing in downtown – Developer fees, impact bonds, and an annual vacancy tax will be necessary to fund rental subsidies to keep impoverished residents of Skid Row housed. In particular, developer fees and a new 1% impact bond for rental subsidies.

● Anti-Displacement Protections – Tenants will need legal representation to fight evictions, combat discrimination by landlords against housing voucher recipients, and pursue anti-harassment penalties for landlords.

In September 2021, broad mobilization of Black, brown, poor, and unhoused residents of downtown has already helped secure some of those demands, with the City Planning Commission agreeing to many of the community’s recommendations, including some of the ones mentioned above. [191] Yet again though, the onslaught of criminalization grows in tandem with these wins. Earlier the same month, the City Council launched another broad attack on Skid Row. On top of the proposed rezoning of Skid Row, the city revamped the notorious Municipal Code 41.18, setting in motion another campaign to criminalize and banish unhoused people.

The displacement launched through revisions of 41.18 will depend on data-driven policing and surveillance too. This law expands criminalization of poverty, and some of its harshest aspects will be activated through zone by zone resolutions passed by the City Council. [192] This framework gives each member of City Council greater powers of population control in their district, marking local zones that LAPD will make uninhabitable for the poor. Surveillance will be crucial to that war, helping politicians and police map their targets zone by zone, block by block, person by person and then use ticketing, sweeps, and destruction of personal property to attack unhoused residents.

Skid Row will be particularly vulnerable to these attacks, but the fight continues. This is not only a fight to remain in the community but a fight to be free.