Real Estate and Capitalist Crisis

Below we share a set of vignettes and questions illustrating the links between capitalist crisis, real estate development, police data, and enforcement of both property and criminal law. When we uncovered these links, it became obvious that real estate developers had a cozy relationship with law enforcement, and we began to research how data-driven policing cements and expands these relationships.

Data-driven policing helps link enforcement of criminal and property laws, especially through programs where policing is used for evictions and land grabs. These links aren’t new of course. Policing and property law have always been instrumental to conquest. Much like today’s use of policing, prosecutions, and real estate development to displace people and continue conquest, “colonial conflict was driven by economic incentives, and was racially structured and entangled with civil laws.” [93] Today those relations – inscribed into U.S. laws and established in legal powers granted to police, prosecutors, and landowners by colonizers centuries ago – continue to shape management, control, and theft of land. Indeed much of U.S. property law was originally written to help Europeans manage their conquest of land and ownership of people. [94]

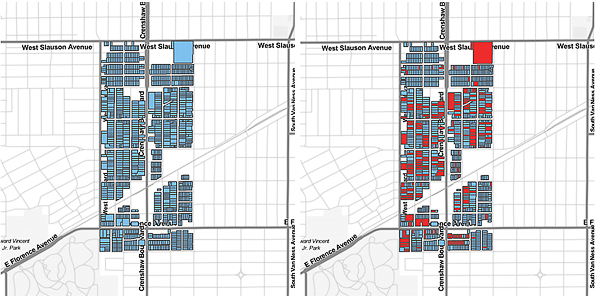

Capitalism, law, and conquest continue to act in combination today. After the 2008 financial crisis, Los Angeles became the site of aggressive land grabs by corporate landlords acquiring distressed residential properties. [95] As a result, a small class of investors and corporations now control a large part of the housing market through the financial system. [96] An examination of residential property ownership (specifically, parcels registered as “Residential” use type) in a LASER zone along the Crenshaw Corridor from Slauson Avenue to just south of Florence Avenue illustrates this corporate takeover. The LASER zone includes 1,061 residential parcels amounting to over 4,550 housing units. In that same area, a total of 194 parcels are owned by corporate entities, translating to over 2,135 units—nearly half of all housing in the neighborhood. [97] When we looked up the date of acquisition for these corporate-owned parcels, we found that 76% were bought after 2008.

How cozy are these corporate landlords with LAPD?

One of the many new entities that emerged during the Great Recession is Haroni Investments, owned by Adir Haroni and Amir Ohebsion. Formed in February 2011, Haroni Investments is one of many investors driving gentrification in South Central, capitalizing on banishment of Black and brown people. Haroni Investments has been developing several new apartment buildings in South Central near the newly under construction SoFi stadium as well as around the new Crenshaw line – two mega-projects driving displacement in South Central Los Angeles.

Email communications that we obtained through PRA requests reveal a close level of familiarity and collaboration between Haroni’s owner Amir Ohebsian and law enforcement officials. [99] In the emails, which are from late 2018, a city prosecutor wrote to LAPD saying he “is working on a property in 77th Division and the owner emailed me about trouble he is having at a different property in Rampart.” An LAPD officer promptly responded, “give me the details of the issue so that I can and [sic] put them in our database.” The prosecutor then shared Ohebsion’s email and the building address and said, “I will give the owner your contact information and ask him to reach out to you.”

The owner referenced here is Haroni’s Amir Ohebsion. And the prosecutor worked in the CNAP program. Research into every CNAP case filed by the City Attorney between 2013 and 2018 – some of the prime years of real estate speculation following the Great Recession – show that CNAP prosecutors “mostly target housing, be it single-family dwellings or multi-family rental buildings, and residential hotels and motels” and a “large number of these properties are located in South Central Los Angeles, specifically in census tracts where Black residents make up 30% or more of the population.” [100]

These links let us to study data-driven policing’s role in gentrification in South Central, a community that has long been subject to LAPD terror and experimentation. We share more on that topic in part 5 of this report.

How do LAPD and developers contribute to “nuisance abatement”?

The city claims that the purpose of the CNAP program is to target “the worst abandoned structures and nuisance properties plaguing Los Angeles.” [101] But as the interaction between CNAP prosecutors and real estate investors reveal, this program is another instrument by which policing targets communities to make way for gentrification. The City Attorney accomplishes this through mechanisms of both property law and criminal law, which have long been combined as weapons of racial conquest and segregation.

The City Attorney’s office, which introduced Haroni owner Amir Ohebsion to LAPD and its database, has also been linked to predictive policing from early on. For example, in March 2016 a “Neighborhood Prosecutor” for the Harbor Division emailed Craig Uchida, the LAPD consultant who built Operation LASER, that she was “looking for stats on how the three LASER zones were identified for the Harbor Division.” [102] Uchida replied, sending her the data with a caveat: “Usually I don’t send the data, but here they are.” Uchida also requested that she “not distribute the data,” explaining that the zones “are unvalidated.” The prosecutor responded that she was “working with LAPD to assist in any way we can with enforcement of the LASER zones,” and the unvalidated data “will be very helpful since I have been meeting with the three senior lead officers to formulate strategies regarding our enforcement efforts in their respective areas.” About Uchida’s warnings not to share the data, she added: “It will only be used to strategize and will not be distributed.”

Two months after that exchange, a different City Attorney supervisor for the City Attorney’s Harbor Branch emailed an LAPD Harbor Area officer to ask, “Please advise me how the police reports coming out of the Laser areas are being marked for review.” Four days later the LAPD Harbor Area officer responded, “The laser project has been initiated. When we receive an arrest in the laser zones the report will have a red L in the top right corner as requested.” The Supervising Attorney wrote back, “This is wonderful news!” With that, the strategy was in motion.

CNAP prosecutors also appear to coordinate with local and federal law enforcement through fusion centers. A February 2018 email from Jonathan Cristall, Supervising Assistant City Attorney for CNAP, addressed “Hey Team,” announced that “we’ll be getting a tour” of the JRIC with an LAPD officer. Cristall’s email was sent to an email list named “ATT TOUGH,” referring to T.O.U.G.H (Taking Out Urban Gang Headquarters). This is a project that Cristall supervises and wrote about in a report from the federal Bureau of Justice Assistance advising prosecutors across the country to use property law to pressure landlords into evicting unwanted tenants. The report noted that “attorneys assigned to T.O.U.G.H. are criminal prosecutors” and in the next sentence boasted that one of “several benefits to this” approach is that “the defendants do not have a right to a jury trial or a court-appointed attorney.”

One of the T.O.U.G.H. prosecutors who Cristal invited on the JRIC spy center tour was Drew Robertson, a Deputy City Attorney. Court records show coordination between Robertson and real estate developer Shaul Kuba to use CNAP to coerce Abdul Sherif, the owner of a liquor store in rapidly gentrifying West Adams, to sell Kuba his business. [103] Kuba is the Israeli-American co-founder of CIM Group, a real estate firm worth over $30 billion and described in 2009 as “Hollywood’s richest slumlord.” [104] CIM is known for taking over distressed properties in gentrifying areas and had been a leading contender to purchase the Crenshaw Mall, a move widely opposed by Black residents of South Central L.A. and eventually blocked. [105]

In 2018, CIM Group was developing at least six sites within a few blocks of Sherif’s store. This case shows how CNAP is used to compel private-public “partnership” on LAPD surveillance. Depositions from the case show that the lawsuit was used to pressure the owner to install street-facing surveillance cameras that an undercover officer confirmed LAPD has access to. [106] The undercover officer – who was assigned to the West Adams area – also confirmed that this LAPD access to private cameras was “in keeping with [his] recommendation in other situations.”

Discovering examples like this made us eager to learn more about the exact collaboration between CNAP prosecutors and LAPD, as well as between law enforcement and landlords like Haroni and CIM.

How are these landlords transforming these neighborhoods?

Let’s return to Haroni and the foreclosure crisis. As the crisis slowed, Haroni began capitalizing on the gentrification arriving in South Central by buying foreclosed properties and developing market-rate housing promoted as luxury rentals. While corporate Wall Street landlords targeted primarily single-family homes during this time, entities like Haroni preyed on the acquisition of three-to-six unit properties – what are typically understood to be owned by “mom-and-pop” landlords. Haroni’s first foreclosed acquisition in February 2011 was a triplex near Jefferson Park whose previous landlord, an individual person, had owned the property and been part of the neighborhood since 1994. In the two-year period from 2011 to 2012, Haroni acquired a total of 37 foreclosed properties amounting to over 155 units.

Haroni’s business in South Central reveals a neoliberal approach to housing access, along with distinctly colonialist dynamics: developers use market subsidy housing policies and nonprofit organizations to fund and launder their private land grab. For instance, Haroni’s first developments, completed in 2016 and 2018, are a three story 37-unit apartment complex on Figueroa and 83rd Street and a 50-plus apartment complex near the Crenshaw Corridor on Hyde Park Boulevard and Brynhurst Avenue. Both developments include the bare minimum required by California’s density bonus law. And in what amounts to a strategy of attrition, the partnerships between developers, nonprofits, and politicians upholding gentrification-friendly policies enact what Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor calls “predatory inclusion.” [107]

Some of Haroni’s units are leased in collaboration with the nonprofit Brilliant Corners, which reported over $225 million in assets in its last publicly available tax filings, a massive increase from $128 million the previous year. [108] Brilliant Corners enters into contracts with developers to house people typically rejected by landlords, including community members who have survived incarceration and policing. These contracts pay top market dollar, underwritten by state subsidy programs that can include MediCal funding and extend for a five or ten year span after a new building is constructed, helping cover the development cost. Including low-income households in new developments allows investors to appear as if they are providing housing access. And even the roots of the problem these programs address – homelessness, housing insecurity, poverty – are of course the intentional result of the state’s political choices around policing and incarceration.

Instead of guaranteeing people permanent homes, this model ends up lining the pockets of landlords, stabilizing their real estate speculation. As Haroni’s Amir Ohebsion himself put it, “From our perspective as a for profit developer, Brilliant Corners has been a phenomenal partner. They provide a reliable income stream on their leased units which minimizes our vacancy rate and mitigates our collection risks and related overhead typically associated with collections.” [109] Finally, when subsidies inevitably expire, both low-income households and municipal agencies are held hostage in a potentially exploitative process that allows developers to temporarily ease into an area with the goal of fully transforming them for profit.

A closer look at some of Haroni’s properties in the area reveals this “predatory inclusion” at work. The materializing Metro Crenshaw Line has set in motion for speculators to use the Ellis Act to demolish existing housing stock and build exclusionary luxury properties in their place. In July 2016, Haroni acquired a fourplex on Crenshaw Boulevard, between 60th and 63rd, where the Metro line will run (Photo 1 above). A year later, the developer filed to raze the building. What then arose is a 75-unit project that includes a bare minimum of low income units (Photo 2), with a Now Leasing banner promising “luxurious secure apartments” (Photo 3).

While the word “luxurious” is commonly used by housing developers to advertise units in gentrifying neighborhoods, perhaps more revealing is the word “secure.” Haroni’s business behavior and direct line of communication with the City Attorney’s office to request LAPD intervention suggests that they are in the business of selling a “new” South Central that comes with “security,” enforced through police banishment of undesirable Black and brown bodies. Although the median rent in the area is $1,072, [110] the asking price for a one-bedroom unit at the property was nearly double, at $1,900 as of late 2020. [111] As always, this land is only “secure” for some.

How does LAPD collaborate with Business Improvement Districts?

In December 2018, Tia Strozier sent an email to George Yu: “So nice to meet you this morning! I look forward to working with you soon. Let’s plan on doing a walk-along in Chinatown sometime during the week of January 7th if that works for you. Have a great day!” Strozier is the City Attorney’s “Neighborhood Prosecutor” for LAPD’s Central Division, and Yu is a real estate developer who runs the Chinatown Business Improvement District (BID), which over the past few years has spent millions of dollars on a private security force to patrol Chinatown. A couple months after that email, Strozier wrote to Yu again, saying she would “like to attend your next BID board meeting” and asking for a calendar of future events. [112]

As Strozier and Yu got to know each other, their communications took on more specific targets. In May 2019, the two strategized on how to harass unsheltered Chinatown resident and activist Theo Henderson. Strozier offered her office’s powers to remove Henderson from the neighborhood, and Yu arranged for Elizabeth Ortega, LAPD’s Senior Lead Officer for the Chinatown area, to tell Henderson that she would be “pursuing stay away orders” to banish him from a public park. A few months later, Yu emailed Strozier and Ortega photographs of another unhoused Black man, referring to him as “male transient EDWARD.” The next day, Ortega responded: “We did facial recognition and found out his info.” She also noted that “he appears gravely disabled,” to which Yu responded: “I fully understand the current rules of engagement and will remind all when Edward is either struck by a vehicle or something catches on fire.”

These examples illustrate how BIDs make use of LAPD relationships to localize and narrow the focus of policing against individuals. BIDs have been present in Los Angeles since 1994, currently numbering around 40. While BIDs appear to be public entities, they are in fact privately run. Funded through 501(c)(3) organizations that depend on tax-deductible donations from real estate developers, BIDs form direct communication links between police, prosecutors, and real estate developers. Many BIDs hire private security that double as a personal police force for local property owners as well as an auxiliary police force for LAPD. As the example of George Yu and facial recognition above shows, BIDs help expand the reach of LAPD’s architecture of surveillance, and they embed policing even deeper in the property interests of developers, businesses, and landlords.

The majority of BIDs in Los Angeles are “property” BIDs, meaning their membership is property owners rather than the merchants of the area. These members pay assessments to the BID, and they sometimes pass the costs to their tenants. This structure is deliberate: concentrating the BID’s power within those who ownthe property rather than those who own the businesses within means that developers are the ones policing the street. BIDs are a way for these developers to use both public and private police forces to remake Los Angeles in their image.

George Yu and other members of the Chinatown BID are predatory developers who do not represent the interests of Chinatown’s longtime residents. Yu himself is a vice president of Macco Investment Corporation, which manages Far East Plaza, promoted as a “Hipster Food Heaven.” [113] These restaurants and new businesses are not intended to cater to the community, instead fueling the displacement of existing working class, multiracial, immigrant communities who are gentrified out of the community. Development like this “raises the price of living and operating for the neighborhood’s original working-class tenants and businesses who are eventually priced out, displaced, and forced to live and work elsewhere.” [114] Other members of the Chinatown BID include Jennifer Kim, a representative of the developer that built Blossom Plaza, a massive 237 luxury apartment complex in Chinatown; Jenni Harris, a representative from Atlas Capital Group, which is in the process of developing a massive 700-unit luxury building with no affordable housing right outside of the Metro’s Chinatown station; and Thomas Majich, a representative from Red Car, which has bought and flipped multiple plots of land in Chinatown. [115]

The deep relationships between the Chinatown BID, developers, and LAPD has allowed these entities to work in tandem to displace Chinatown’s working class, immigrant communities. BIDs also exchange surveillance, including by hiring the same private security firms (such as Allied Universal) and through LAPD networks. For example, in 2018, LAPD monitored the social media accounts of Code Pink activists and forwarded that information to two downtown BIDs and Allied Universal Security. [116] In addition, BIDs received regular lists of hot spots from PredPol, [117] and, as discussed in part 4, a set of LASER’s anchor points around Skid Row were marked by LAPD as “BID Anchor Points.” [118]

BIDs also fight back efforts at community empowerment. When Skid Row residents organized to create a Neighborhood Council separate from the two existing downtown Councils, two BIDs mounted an aggressive opposition campaign, [119] which included an unprecedented move to take voting online. The efforts of BIDs in harassing unsheltered people extends beyond what goes on in the streets, directly into the systems through which state power is distributed. In the next part of the report, we examine these fights in Skid Row, where the community has long been fighting back coordination between police, developers, and BIDs to displace them from their homes.